Through my rosé-colored lenses, one of the greatest dividends of travel is the ability to take advantage of the diversity of wines now available. By diversity I mean not only the astonishing range of grapes, regions, and styles now on shelves and wine lists, but also the pleasure that can be had at both ends of the price continuum. No experience better captures this truth than a day last month in San Francisco.

Through my rosé-colored lenses, one of the greatest dividends of travel is the ability to take advantage of the diversity of wines now available. By diversity I mean not only the astonishing range of grapes, regions, and styles now on shelves and wine lists, but also the pleasure that can be had at both ends of the price continuum. No experience better captures this truth than a day last month in San Francisco.

It started with my first visit to Swan’s Oyster Depot, a timeworn feeding station as unapologetically simple as the oyster crackers that accompany your food. With its rickety stools, homespun menu board, and no-nonsense countermen, Swan’s has the feel of a San Francisco drugstore soda fountain, albeit one plopped down in the middle of a seedy city block; if Dirty Harry knew his way around a bivalve, this is where his day would be made.

We started with buttery Kumamotos accented with house-made mignonette sauce, then devoured cocktails of impossibly fresh Dungeness crabmeat — meaty, sweet, and pure. In just a few bites, this glistening fare provided cosmic retribution for every Filet-o-Fish sandwich ever to roll off the conveyer belt.

What really catapulted this lunch to “eleven” was the addition of wine — nothing expensive or complex but lean and piercing glasses of $7 Château la Tarciere Muscadet from France’s Loire Valley. Muscadet can be disappointingly bland to flavor-cravers accustomed to high-octane Chardonnay. But with shellfish, a well-made Muscadet operates like a lemon-squeeze or a spoonful of mignonette sauce, heightening flavors and making oceanic creatures taste richer and sweeter. It may not be a party sipper to be savored by itself, but with seafood of Swan’s caliber a good Muscadet is one of life’s deep pleasures.

If daytime brought ecstasy through modest means, nighttime provided a onetime pass to the gastronomic equivalent of Avatar’s Planet Pandora. But instead of reveling in the movie’s luminescent creatures, twelve fortunate wine lovers and I were treated to something even more extraordinary: a dinner featuring the wines of Henri Jayer from 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s, twelve different bottles in all, including one magnum. Organized by a collector whose taste and bonhomie is as epic as his generosity, these wines are the vinous equal of an Iberian Linx: you might read about its magnificence in magazines but you doubt that it actually exists in the material world. If the celebrated premier cru Bordeaux Chateau Margaux is like a late-model Bentley – regal, powerful, but relatively prevalent on certain streets — Jayer’s best vintages are like a ‘30s Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Roadster: finely styled, achingly beautiful, and so rare that many pros wouldn’t even know where to find one.

Considered to be one history’s greatest fermenters of the grape, Henri Jayer, who died in 2006 at the age of 84, made Pinot Noir from Burgundy vineyards of microscopic size and monumental quality. He was especially noted for his pioneering vineyard practices and for performing them with a minimum of assistance. As one of my fellow guests related it, when a visitor to Jayer’s vineyards saw his sparsely populated winery, he demanded of the legendary vigeron, “Who helps you with all of this?”

With a twinkle in his eye, Jayer replied: “Les deux mains” (“My two hands.”)

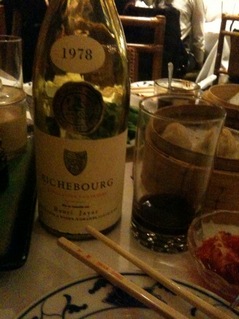

And what those hands wrought. While words fail to adequately capture the sensations that aged Burgundy of this caliber can offer, suffice it to say that this was one of those rare instances when wine achieves the ethereal. As you sit with the wine, your nose inhales kaleidoscopic aromas of red berries, violets, Asian spices, earth, and smoke. These and other notes echo on the palate, joined by an enduring velvetiness that rivals the pleasure of a long, intense back scratch. The ‘78 Richebourg was especially commanding, its nose voluptuous with hints of cassis, rose water, and nutmeg, and its texture hauntingly vibrant and silky. It is not overstating the case to say that this was one of the best wines ever to pass my lips. I’m convinced that many of the world’s mood disorders would vanish if that Riche’s essence could somehow be captured and added to the world’s water supplies.

Like the Avatar audiences for whom reality pales next to the sensory splendor of Pandora, no one wanted this dinner to end. But the bottles were eventually drained and so I said my goodbyes and shuffled my lucky bones back to my hotel, easing my reentry into reality by toting along the empty bottle of Richebourg.

I probably wouldn’t have believed this night in San Francisco had transpired it if I didn’t wake up the next morning with that bottle watching over me. Its existence was a comforting sight, and then I looked closer: a few mouthfuls remained in the bottle! No matter that the sommelier had intentionally withheld this sediment-saturated juice; it could have been Tijuana tap water and I still was going to make productive use of it.

So I slipped the bottle into a discreet bag and walked two blocks to Yank Sing, San Francisco’s venerable dim sum house. When the frenetic trolley dollies weren’t looking our way, a friend and I took turns sipping the remains of the Richebourg, completely unbothered by the flecks of sediment swirling in our glasses like snow shakers. As we relished the wine with bites of soup dumplings, I contemplated the previous 24 hours in San Francisco and how ecstasy was found, by turns, in the simple, the sublime, and now a bit of both at the same time

Originally appearing on Tablet.com