As a wine writer, I see my mission as building a bridge between wine pros and the innumerable folks who feel like they know nothing about wine. What I never expected, however, is that this bridge would lead me straight to criminal court.

It began innocently enough at a dinner at Colicchio & Sons in the Meatpacking district in honor of a friend’s engagement. Being a wine enthusiast, he had arranged for several special bottles for those in attendance.

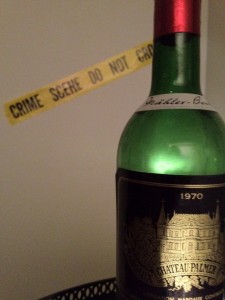

A merry time was had by all, and as we exited the restaurant, I spotted one of the finished bottles, empty save for a half inch of undrinkable sediment wash, which is the guck that remains in an old bottle after it is decanted. The wine was a 1970 Chateau Palmer, a rarity whose taste was as magnificent as its striking, gold-and-black label. Its plums-and-truffle perfume and enduringly silky, savory finish is forever etched in my mind. Grape nuts like me hold on to these so-called “dead soldiers” like a moonstruck Iroquoi would collect scalps—part keepsake, part trophy, part talisman. I scooped it up and headed outside.

In the crosswalk mere seconds later, I heard the squawk of a police siren, followed by a stern, amplified directive to move to the sidewalk. A police spotlight traced my steps as I froze and shuffled to the curb, the light blazing in my eyes as if I were an escaped convict. Is this really what happens when you don’t pay your E-ZPASS?

My friends – good friends that they are — scattered like confetti. The cops drove their squad car over to me, rolled down the window, and asked what I was carrying.

An empty wine bottle, I explained, just a keepsake that I was toting home from dinner. They asked to see it, and spied the smidgen of liquid inside. They started writing me up.

“No, no, that’s just sediment. It’s what left after you decant a mature bottle…“ My voice trailed off as I realized that this explanation was about as futile as trying to teach them the art of miming.

I stood there, resigned to perp status, until one of my friends returned to the scene and informed them that I was a wine writer. That and the fact that the bottle didn’t look like typical swill must have made them realize that perhaps they were acting in error. They exited their cruiser, their manner noticeably warmer.

“Ok, so this is what you do,” said one. “The summons we’re issuing you requires a mandatory court appearance, but all need to do is go down to the courthouse, plead guilty, and pay a $25 fine. Nothing more. And it won’t go on your record.”

Grateful for this conciliatory act, I thanked them, took the summons and the offending bottle, and caught up with the rest of the group. For the rest of the night, I posed for photos with the bottle, cradling it in different positions as if we were lovers in a photo booth. I marveled that of any time to be issued an open container summons, it happened in the rare instance in which I was packing a 40-year-old bottle of fine Bordeaux. Finally, a Tweetable moment.

Then the indignation set in: why should I plead guilty? I was innocent and so was the bottle. I resolved to fight.

It took a few months for the case to wend its way through the system, but when it finally did, I was ready for court, though the venue itself was eye-opening. The courtroom was not the sleek chamber of Hollywood dramas but a dilapidated cuckoo’s nest populated with the hangdog faces, scruffy denim, and tobacco reek of reckless drivers, public urinators, and the domestically violent.

When the bailiff called my name, I walked to podium, fortified with a suit, tie, and my latest book.

As indicated above, the judge needed some time to process that wine writing was actually a job, but once he did, his curiosity ran high. Do I write about the wine before or after I drink it? Am I French? What was the most amount of wine I ever drank in a day? Do I know of Night Train?

When the bailiff showed him my book, he paged through it approvingly.

“You can have it,” I offered, figuring that it would be a donation to a good cause.

“No!” chided the court-assigned lawyer standing beside me. “That would be bribing the judge.”

The judge’s next question revealed the full extent of his affability: “How did you get to be an expert in drinking wine? I’m looking for another career. I’m going to retire.”

Finally, he wanted to know which kinds of wine were most ageable. As I answered, the surreality of having to teach an extemporaneous wine lesson – not only to the judge and court staff, but also, indirectly, to my fellow accused in the room – was not lost on me.

The judge flashed me a satisfied glance, and laid down his gavel. Case dismissed, along with my liability for walking the streets with an unloaded bottle of Bordeaux.